What? So What? Now What...

THE PUZZLE OF THE HUMAN BRAIN

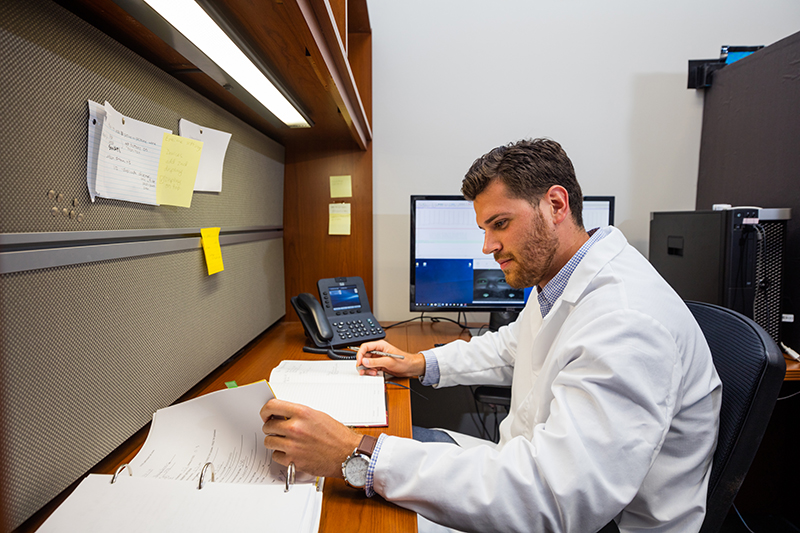

Behavioral neuroscientist, Dr. Rodney Roosevelt, was fully engrossed in his professor role as he sat in his office after finals. Associate professor of psychology at ATU for the past two years, Roosevelt had a red pen in his pocket and spreadsheets open on his computer screen. In his office, metal shelving stood in the corner holding stacks of paper and wrapped plastic test tubes.

When asked about his research, Roosevelt’s face lit up. “Part of being a citizen is understanding the need for research,” he said. “Research provides citizens with the information they need to make informed choices.”

One of his key areas of research is vagus nerve stimulation. In the past, vagus nerve stimulation could only happen through surgery on the carotid artery sheath in the neck, but with technology, there are new discoveries. The vagus nerve connects the brain to the body and controls several critical functions, including heart rate, digestion in the body and influences emotion and cognition. More recently a previously unknown branch of the nerve was located at the surface of the ear, making it accessible for study.

“[The vagus nerve] had just never been mapped or mapped well, so there’s a big fight going on now, if it’s actually the vagus or not. But what happens is this nerve comes up to the surface of the ear, which means I can get at it,” said Roosevelt. “I can electrically stimulate [the nerve] without surgery, which is a big bonus. Now the big race is on at universities all around the planet to see what’s going on with this nerve.”

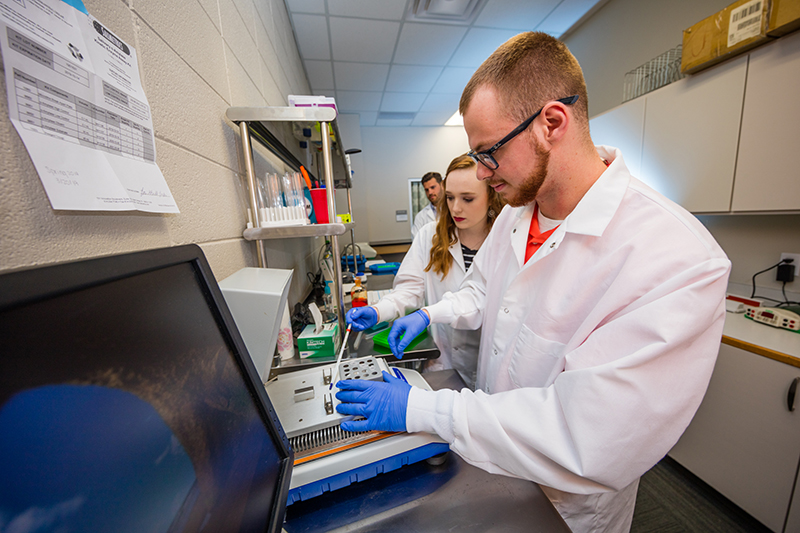

Under the direction of Roosevelt, three ATU students recently presented a pair of posters at the 2019 Southwestern Psychological Association Conference April 5-7 in Albuquerque, N.M. Senior Grant Collier of Russellville, graduate student Brooke Harris of El Dorado and graduate student Dylan Shelton of Cedarville offered information about the effects of intermittent transdermal vagus nerve stimulation on heart rate variability in humans.

“The problem is, we only know how vagus stimulation works in people who are damaged,” said Roosevelt. Currently, vagus nerve stimulation is approved for epilepsy treatment and approved for the treatment of certain types of depression.

“There [are] all these potential applications, but we can’t study it in humans, because we can’t figure out how to how to do it,” said Roosevelt. This is where research comes in—to figure out how to utilize vagus nerve stimulation for help with treatment for head trauma and stroke rehabilitation.

“[The research] is kind of a frontier thing—it could be five years from now—it could be accepted practice everywhere, or it could be one of those things that end[s] up in the dustbin of history, but that’s how science works,” said Roosevelt.

When asked how he became interested in his line of work, Roosevelt referenced being a former rock climber and said, with a chuckle, “I stumbled into it.”

With plans to eventually go to medical school, Roosevelt became interested in the human brain while gaining clinical hours in a head trauma research laboratory after having worked as a firefighter and EMT. It was in the laboratory setting that Roosevelt realized his genuine interest in the puzzle-solving aspect of neuroscience and human behavior rather than what most people think of when they hear the term “psychology.”

“Our brains are kind of bad drivers with one foot on the gas, one on the brake all the time,” continued Roosevelt. “And so, there’s this dynamic balance—the reason that’s important is if I increase the braking in one area, it’s going to amplify (functionally) the activity in another [area]. Another way to think about it is if you think about radios, and you’re trying to tune them in and get two competing stations on frequencies right beside each other.”

He chose to continue his study through the doctoral level to become a college professor rather than go to medical school. At the time Roosevelt sought out employment at Arkansas Tech University, he wanted a place in a smaller regional university because he felt he could make the most difference to students in that environment—an environment where research is needed.

A lot of his work focuses on getting students to ask the following questions: What, so what, and now what? Once students know what to study, Roosevelt helps them with the final questions about why their subject or problem is important.

It was Roosevelt’s persistence that led to a lab for his research at ATU. Originally told there was no room, Roosevelt eventually found a place near his office and cobbled together enough equipment along with what he’d brought with him from previous research work. “Sometimes you have to be unreasonably persistent to make progress,” he said.

Because of Roosevelt’s steadfastness, students in the psychology program were able to participate in ATU’s first ever clinical trial. He wanted to help influence students who will go on to change the world. “I’m a practitioner in my profession,” he said. “I just think that’s so important. I think our students deserve practitioners in their professions.”

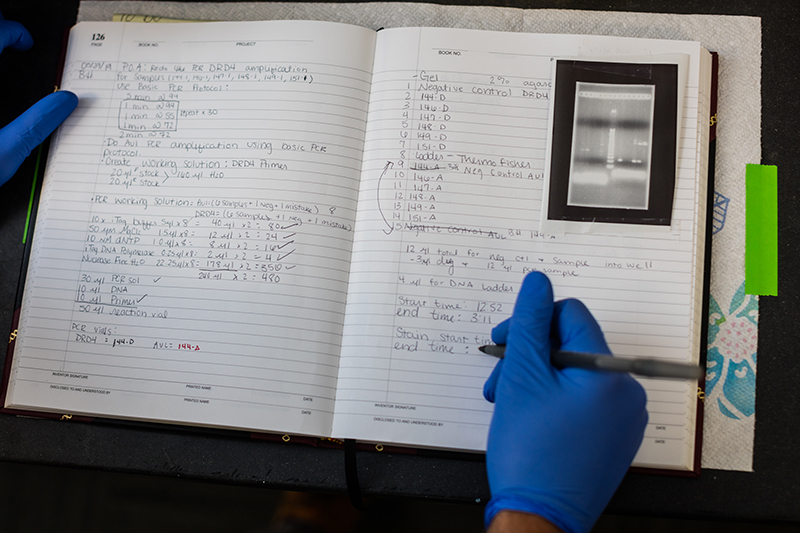

Other studies conducted in the Psychology Department include DNA research and social network modeling. Research done at schools like ATU goes with students as they further their education in medical school and graduate school at larger research institutions granting master’s and doctoral degrees.

Roosevelt’s goal is for students to possess three skills after his mentorship: Ability to communicate—particularly in writing, the ability to apply critical thinking skills and the ability to work well with others. He also stresses the general applicability of the three skills to non-academic settings.

“Students are agents of change,” said Roosevelt. “Deeply engaged students take ownership of their learning. My philosophy is to give students a place where they can grow organically and [then] get out of their way as they find their paths forward.”